When a "rare variant" isn't actually rare

A lack of genetic database diversity highlights red herrings in disease diagnosis

Each of our genomes has approximately 3 billion base pairs.

So, when it comes to diagnosing likely genetic diseases, there's a lot of data to dig through.

That's because those 3 billion base pairs aren't the same in all of us.

We have variants that are unique to us as individuals and variants that are unique to each of our ancestries.

This means that if we compare my genome to your genome, we're going to see A LOT of differences in them.

Like, millions of differences!

And we know this because when we compare individual genomes to the standard reference genome that was sequenced as a part of the human genome project, we find, on average: 5 million single nucleotide variants (SNVs), 600,000 small insertions/deletions (indels), and 25,000 structural variants (SVs).

So you can imagine that trying to figure out which of those millions of variants could be the cause of disease in an individual is pretty challenging!

But we do have tools at our disposal, and when someone presents to a clinic with a likely genetic disease, there's a lot to consider.

Clinicians take into account things like phenotype or the visible features of a disease, or if there's a family history of disease, they try to determine the inheritance model (dominant/recessive).

This information is then used to decide what genetic mutations best fit with a disease.

For example, you wouldn't pick variants in genes that aren't directly related to a disease phenotype, nor would you pick genes whose impacts don't match the inheritance model.

But how do you even know that a variant could even be problematic?

Well, we look at whether variants are "damaging" and this is usually a measure of how much a variant potentially could change the structure of an expressed protein.

So things like deletions, insertions, and splice site mutations are typically the most damaging, but SNVs can also alter the function of proteins.

We also look at how well conserved sequences are across the tree of life, and mutations in highly conserved regions are usually prioritized over mutations in regions that aren't as well conserved.

The thinking here being that if a region of the genome hasn't seen much change over time, it's probably important!

But now that we have high throughput whole genome sequencing, and have sequenced many individuals across ancestries, we've seen that each ancestry has its own conserved variants.

This makes figuring out which variants could be causal of disease extremely challenging!

That's because the frequency of a particular variant could be low and highly damaging in one population, or that same exact variant could be common and totally benign in another!

This is why diversity in genetic databases is so important, because it allows us to refine our variant classifications based on ancestry and help us pick out which variants (out of millions) are most likely to be causing someone's disease.

And this isn't just some unsubstantiated concern in the field of clinical genetics.

We know for a fact that the case solve rate is much lower in non-white populations because we just don't have good enough information to make confident guesses about a variant's disease status in other populations that haven't been sequenced as much.

And if we don't have diverse databases, we also run the risk of calling some of those benign ancestral variants as disease causal!

A good example of this problem was recently published in the European Heart Journal where two unrelated patients of Oceanian ancestry presented to an Australian clinic with cardiac phenotypes and it was discovered that they both had the same mutation (c.571-1G>A) in Cardiac troponin T (TNNT2).

Mutations in TNNT2 have been shown to be associated with hypertrophic (HCM) and dilated (DCM) cardiomyopathy so the clinicians here decided to review whether this was a causal variant.

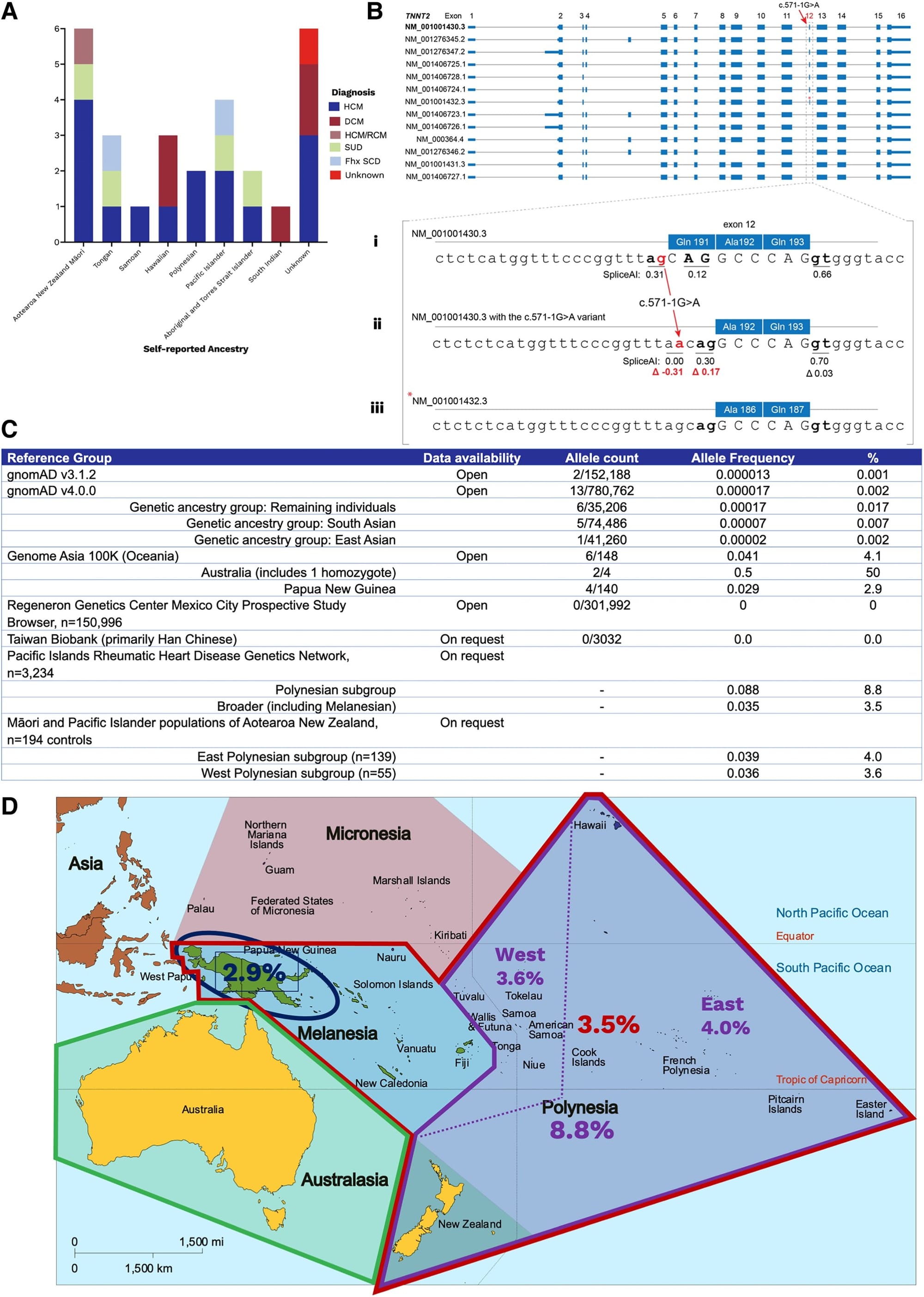

Their workup can be seen in the figure above where in A) they found 26 other unrelated individuals with this variant, many who were of Oceanian descent, B) displays all of the splice variants of TNNT2 - Bi, sequence of the most common splice variant; Bii, highlights the variant in question here; Biii, shows a rarer splice variant and that there's a cryptic splice site that becomes activated in the presence of the mutation in question (compare red numbers) - translation, this variant is well tolerated and doesn't damage the expressed protein, C) is a table of allele frequencies from various databases showing MOST lack enough diversity to accurately classify this variant, D) is a map of Oceana highlighting the high prevalence of the variant in question by region.

This case report is an exquisite example of how variants can be red herrings in genetic diagnosis.

Variants are only considered rare when their population prevalence is <1% and the ACMG recommends classifying a variant as benign if its population prevalence exceeds 5%.

In the Oceanian population, this TNNT2 variant has a prevalence of 3-9%, meaning that as far as variants go, it's pretty common.

Indigenous island populations also have been shown to share about 3% of their DNA with neanderthals and these authors were able to find this variant in two archaic genomes (Vindija and Altai Neanderthal), indicating that it arose 130–145 thousand years ago which helps to explain why this variant is seen in Oceanian populations.

Studies like this underscore the importance of having highly diverse genetic databases and reference genomes that reflect all of the possible ancestral mixtures of variants that we might observe in the clinic.