The discovery of the DNA double-helix was the culmination of decades of work from numerous contributors

History is written by victors, and that statement couldn't be more true than it is in the case of Watson and Crick's 'discovery' of the DNA double helix.

Their structure was published in the April 1953 issue of Nature along with two other papers on the same topic from Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin.

Although they don't cite Franklin in their 1953 paper, they definitely used her data.

It was Franklin's paper that included Raymond Gosling's pristine diffraction of B-DNA, known as Photo 51, that showed the structure of DNA is helical, it's double stranded, and the bases faced inward with the phosphate backbone on the outside.

While this is a good chunk of what you need to know to put the structure of DNA together, there were a couple of additional missing pieces that the boys from the Cavendish Lab had to source.

What gets lost in all of the popular coverage of this discovery is that Watson and Crick didn't perform any experiments, they aggregated the best science at the time to create their model.

Franklin wasn't the only person they borrowed from.

Phoebus Levene's life was spent studying DNA, he's why we call the bases nucleotides and he showed that DNA has a 5'-3' deoxyribose sugar phosphate backbone but also that the bases are composed of adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine.

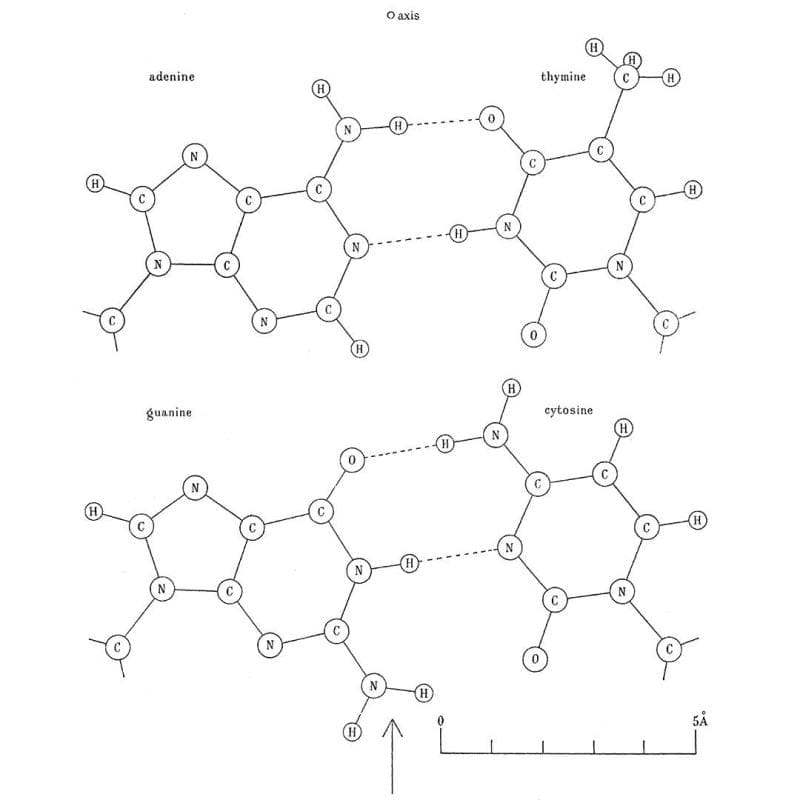

Erwin Chargaff shared with them what he knew about the ratios of the bases, or Chargaff's rule, which is that A and T, and G and C are found paired in a 1:1 ratio.

He had a famously checkered opinion of the duo and even went as far as to say, "I told them all I knew. If they had heard before about the pairing rules, they concealed it. But as they did not seem to know much about anything, I was not unduly surprised."

Next on the list was hydrogen bonding between the bases. This little known fact was cribbed from the thesis work of a graduate student at the time, June Broomhead (Lindsey), who also proposed all of the possible structures for A, T, G and C.

But knowledge of that final piece of the puzzle came from Jerry Donohue who shared an office at Cambridge with Crick.

He noticed that Crick was trying to pair up the bases using their 'enol' forms and so Donohue suggested, based on Broomhead's work, that Crick should try to smash the 'keto' forms together instead because they were much more common.

The image above is Crick's smashing result: Watson-Crick(-Broomhead-Donohue?) base-pairing. It was published in 1954 in a much longer and more detailed follow-up paper on the structure of DNA.

While historic, this story is nuanced, and I'll leave you with Crick's measured interpretation of the situation.

"What, then, do Jim Watson and I deserve credit for? The major credit I think [we] deserve … is for selecting the right problem and sticking to it."

I tend to agree.