The genetics of child sacrifice at Chichén Itzá

Ritual human sacrifice was an important part of ancient Mayan life and now genetics is helping us to identify the origins of those who were sacrificed.

Human sacrifice was a cornerstone of many ancient cultures and generally occurred as a part of their religious practices.

The purpose of these sacrifices was usually to pacify the gods or bring good fortune, be it in the form of success on the battlefield or a good harvest.

Many cultures stopped the practice of ritual human sacrifice before the birth of Christ, but the people living in Central and South America continued the practice up until (and during) the arrival of the Spanish Conquistadors.

For the Mayans (who occupied what is now southern Mexico, Guatemala and Belize), human sacrifice was seen as a way to feed the gods.

One of their best known sacrificial sites, Sacred Cenote, was located at Chichén Itzá, a large Mayan metropolis found on the Yucatán Peninsula.

Here, humans were sacrificed to the rain god Chaac and their remains were placed into a large cenote (a water filled sinkhole).

Over the years, some of these remains have been recovered and studied with archaeologists finding that many of those who were sacrificed were children.

But sacrifices to other gods also occurred at Chichén Itzá and in the late 1960’s, a cistern was uncovered near Sacred Cenote that contained the remains of approximately 100 children.

It was not immediately clear why these children were sacrificed, but now, new DNA evidence is able to give us some clues.

In this paper, the researchers were able to extract ancient DNA from the remains of 64 of the children that were sacrificed.

They found, surprisingly, that ALL of the children were male and many of them appeared to be related.

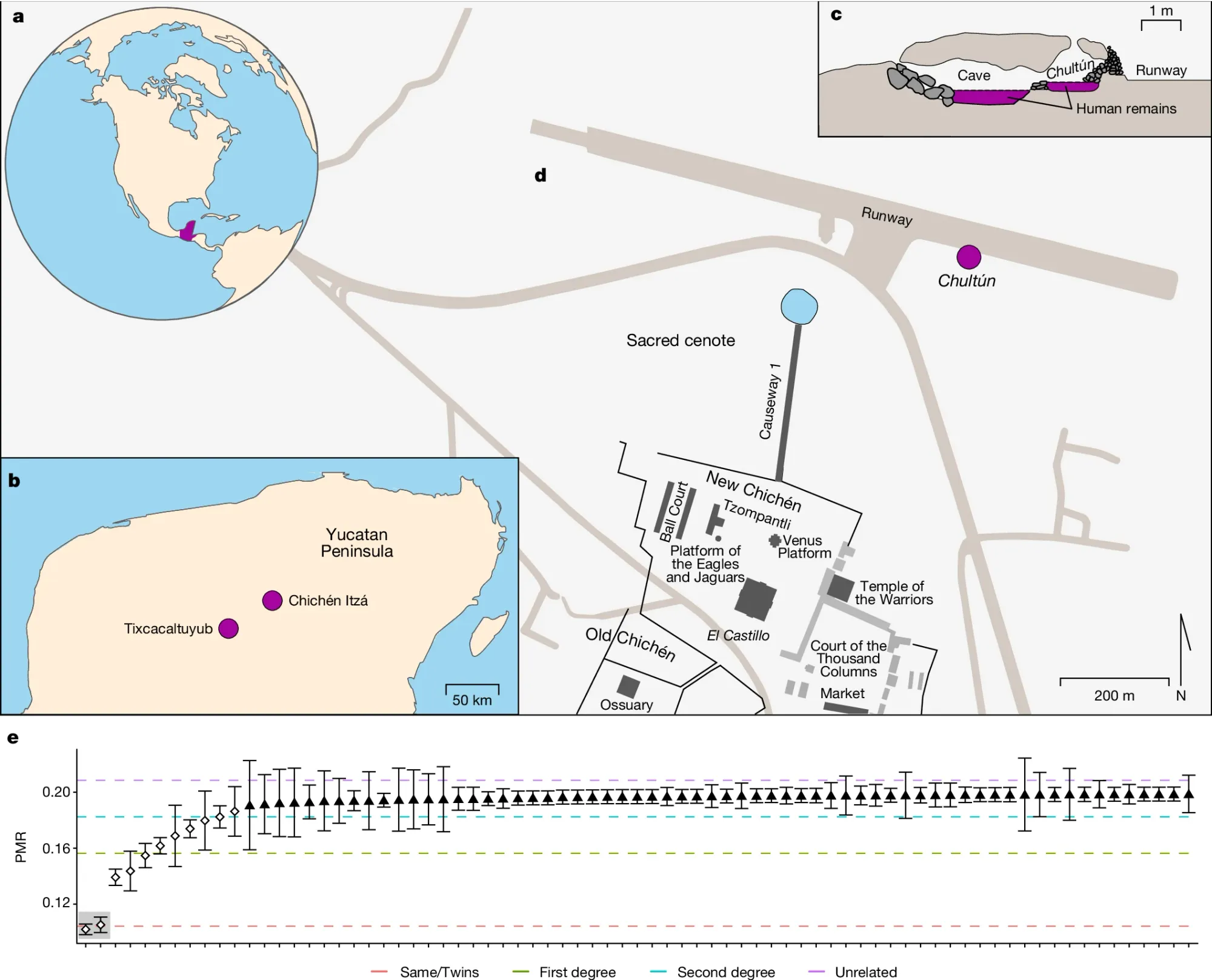

The figure above shows a) the Yucatán Peninsula (a region of current day Mexico) b) location of Chichén Itzá c) the chultún (cistern) where the remains of the children were found d) a map of the complex showing where the chultún was discovered in relation to Sacred Cenote e) the pair-wise mismatch rate (a measure of related-ness) of the 64 specimens including one set of twins (highlighted in gray)

The researchers went on to show that these children were all from local indigenous populations.

But, the discovery of twins and that these children were male and all appeared to be related led the researchers to hypothesize that these children were sacrificed to honor the “Hero Twins,” Hunapu and Xbalanque, who in ancient Mayan lore are reborn every year to avenge their father's death and torment the Gods of the underworld.

The Hero Twins are often depicted in Mayan art as stalks of maize (corn) and these ritual sacrifices could have also been an attempt to bring a good harvest.

Interestingly, because the sacrificial remains found in the chultún spanned approximately 500 years, the researchers were also able to see the effect of epidemics on the genomes of the Maya, noting an increase in the HLA-DR4 allele which confers resistance to "salmonella-derived peptides."