The solid tumor microbiome: friend or foe? Wait, there's a tumor microbiome??

Solid tumors account for the majority of cancers that occur in adults. You might be surprised to know that they also have their own microbiome!

It’s been known for ~100 years that tumors have bacteria associated with them, but studying those bacteria has always been a bit of a challenge.

First of all, the number of bacteria associated with tumors is small and they’re mostly found inside of the tumor cells or the immune cells that infiltrate those tumors.

Secondly, tumor preservation methods make the tumor cells and anything in them non-viable.

So, capturing the bacteria and culturing them to get enough to figure out what was actually in there was basically impossible.

Fortunately, we now can just sequence these samples!

And recent studies have shown that solid tumors can contain highly complex microbial communities.

This is in addition to all of the other things we had to worry about in the tumor microenvironment!

But until now, few studies have looked comprehensively at how those microbiomes change after a primary tumor metastasizes.

It stands to reason that changing the location of a tumor could also change what microbes are associated with it!

This is important because metastases are associated with ~70% of solid tumor cancer deaths.

So, maybe there’s something we can learn about the microbiomes of these killer tumors that we can use against them as a cancer therapy?

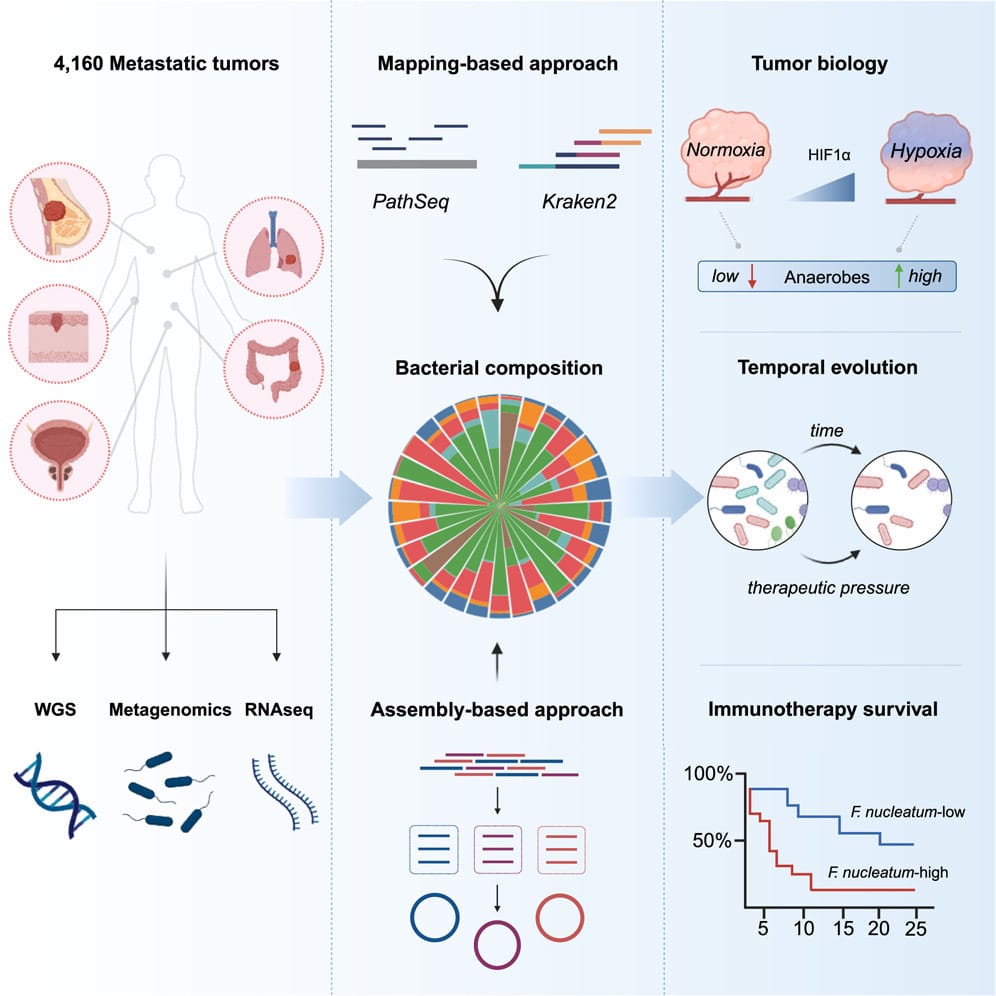

At least that’s the hope, and that’s why the authors of today’s paper chose to look at 4,160 metastatic tumor biopsies from 26 different cancers.

The findings of this study reveal that the tumor microenvironment is extraordinarily complex and that interactions between tumor cells, the immune system and the microbiome can have paradoxical roles in both promoting tumor progression and sensitizing them to therapy.

They used whole genome sequencing and whole transcriptome sequencing to perform a comprehensive metagenomic analysis to reconstruct the microbiomes of each tumor.

They showed that community composition was dependent on metastases location and that these tumors were primarily composed of anaerobes (don't need oxygen).

By comparing tumor microbiomes over time they found that these microbiomes can influence the composition of the tumor microenvironment and the microbiomes themselves can evolve after exposure to therapy.

They also showed that tumors with diverse microbial communities were more responsive to treatment and that high Fusobacterium containing metastases were more resistant to immune checkpoint blockade.

Overall, this study provides insight into the complex role of the metastatic tumor microbiome in cancer biology and therapy response.

The data are also a resource for future research on the potential therapeutic targeting of the metastatic cancer microbiome.