Science has figured out why Garfield is orange

Thanks to some genetic sleuthing, we now understand why orange cats are orange.

Up until now, we only understood why 80% of orange cats were male!

And that’s because orange coat color in cats (and hamsters) is sex-linked.

Sex-linked traits are interesting because they don’t behave entirely the same way that traits that are linked to other chromosomes do.

For the regular old autosomes (the chromosomes who each have two identical copies), the genes that control traits come in pairs.

But with sex chromosomes, things get weird since the X chromosome and Y chromosome are different sizes and carry very different genes!

Biologically female mammals have two X chromosomes whereas biologically male mammals only have one.

This means that males who inherit damaged copies of genes from their moms almost always show a trait because they only get one copy!

But for females to show that same trait, they usually have to inherit two copies.

This simplistic logic holds true in the case of orange coat color in cats which has been shown previously to be linked to the X-chromosome, and this explains why 80% of orange cats are male!

However, we have had no idea how orange coat color in domestic cats was determined on the molecular level.

That changed recently when researchers discovered that orange coat color is caused by a deletion on the X-chromosome that alters the expression of a gene that regulates the production of the melanic pigments, eumelanin and pheomelanin.

Eumelanin is a black to brown pigmentation while pheomelanin is a reddish yellow color.

And it’s the production of these different pigments that give cats their colors and their interesting color patterns!

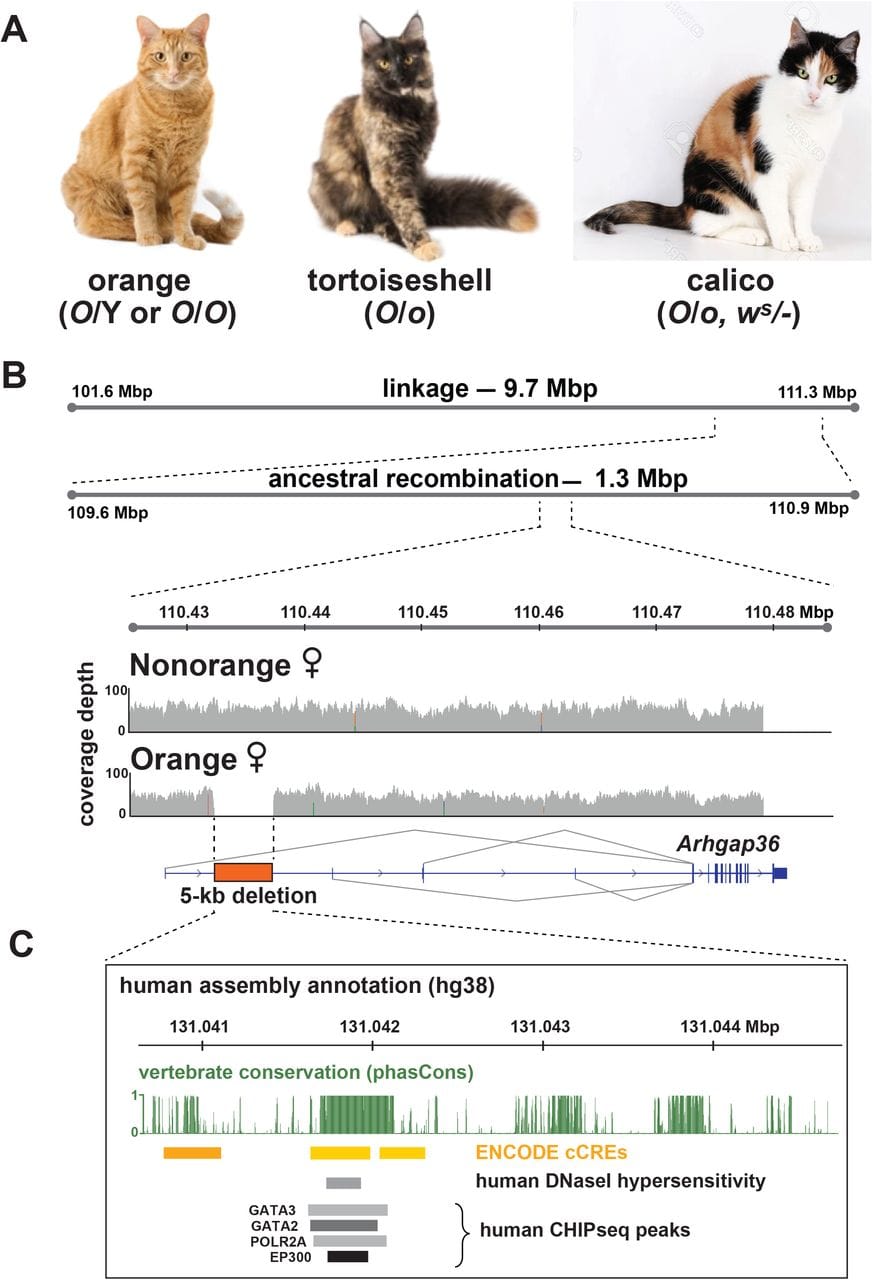

In the figure above the researchers show A) the different color patternings found in domestic cats which include sex-linked orange O/Y (male) and O/O (female), Tortoise shell and calico (which can be the result of X-inactivation based mosaicism and regular old autosomal inheritance) B) Genetic linkage mapping had previously shown that the orange trait was linked to a 9.7 megabase region of the X chromosome but more modern genetic techniques refined that to a 1.3MBp region and this paper further identified an 5kb deletion that was causal of orange coat color in felines. C) While this deletion doesn’t affect the coding region of a gene, it does occur in the non-coding regulatory region of one (see conservation map).

They went on to show that this gene, Rho GTPase Activating Protein 36 (Arhgap36), is upregulated 13 fold in the skin of orange cats.

They also showed that the activities of Arhgap36 result in the inhibition of protein kinase A (PKA), a gene essential for controlling the production of the melanic pigmentation proteins.

In the case of orange cats, this inhibition of PKA by Arhgap36 results in the underproduction of eumelanin (black) and the over production of pheomelanin (red/yellow == orange!).

The results of studies like this are important in the field of genetics because seeing physical traits is only half the story.

And, with respect to disease, if we don’t know the molecular mechanism behind the presentation of a trait, we’ll never be able to come up with treatments to deal with them in the clinic.

This is why basic science research (even in cats) is so important: it gives us the tools to help solve major molecular problems in humans.

Plus, knowing why Garfield is orange (molecularly) is just kinda cool!