Nettie Stevens, a former school teacher turned geneticist, discovered sex chromosomes in 1905. Here's her story:

Nettie Stevens’ contributions to the field of genetics were groundbreaking.

The late 1800s were a turning point in American history for women.

The end of the Civil War marked the start of the women's rights movement and granted them significantly more control over their own lives.

That being said, women were still expected to be teachers or home makers but they won more personal freedom including better access to education.

Stevens took advantage of these expanded liberties, and started her educational pursuits at age 10 studying to become a school teacher.

In 1883, she began a decade-long career in education, filling roles both as a teacher and as a librarian.

However, this wasn't her life's dream, and in 1896, at the age of 34, she had saved enough money to enroll at Stanford University earning both her bachelor's and master's degrees in 1900.

It was during her summer studies that she took a keen interest in cytology while working at the Stanford Marine Lab.

Here she spent her time glued to a microscope and published her first paper on the life-cycle of ciliates in 1901.

Stevens then left Stanford to continue her scientific studies at Bryn Mawr beginning her dissertation work under the guidance of Thomas Hunt Morgan.

You might be familiar with him.

Morgan received the Nobel Prize in 1933 for his work elucidating the role of chromosomes in heredity.

Interestingly, Morgan was initially skeptical of heredity, particularly as it related to sex determination.

At the time, there were two competing hypotheses:

One being that sex was determined by environmental factors, like temperature, and another that sex was inherited as a trait.

In spite of the lingering questions on this topic, Stevens successfully completed her dissertation in 1903, and received an award from the Carnegie Institution to study how sex is determined.

With this funding, Stevens meticulously detailed the cellular structures of the reproductive organs of multiple insects.

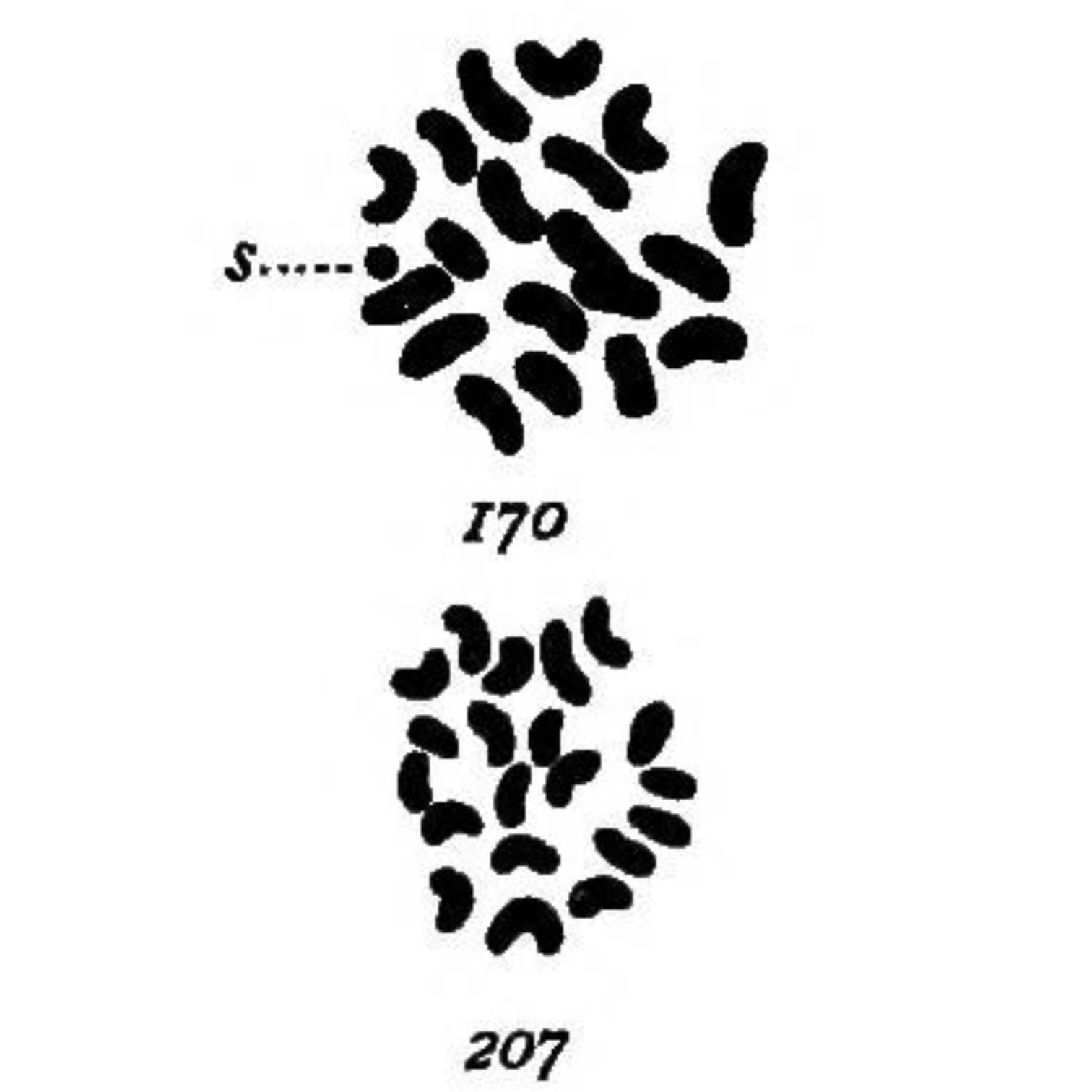

The most striking of these being her drawings in 1905 (see above) of the chromosomes found in mealworms (Tenebrio molitor) where she observed:

‘In both somatic and germ cells of the two sexes there is a difference not in the number of chromatin elements, but in the size of one, which is very small in the male (170-s) and of the same size as the other 19 in the female (207).’

Even though she was the first to make this discovery, Thomas Hunt Morgan and Edmund Beecher Wilson are often incorrectly given the credit.

Tragically, breast cancer cut her scientific career short at the age of 50.

But Nettie Stevens' contributions to our understanding of sex determination, along with her exquisite drawings, were the definition of groundbreaking in the field of genetics.

Read the full issue of Omic.ly Premium 24