A multi-billion dollar industry was spawned from the discovery of circulating free DNA

Two gels spawned a multi-billion dollar industry that didn't exist prior to their publication in 1997.

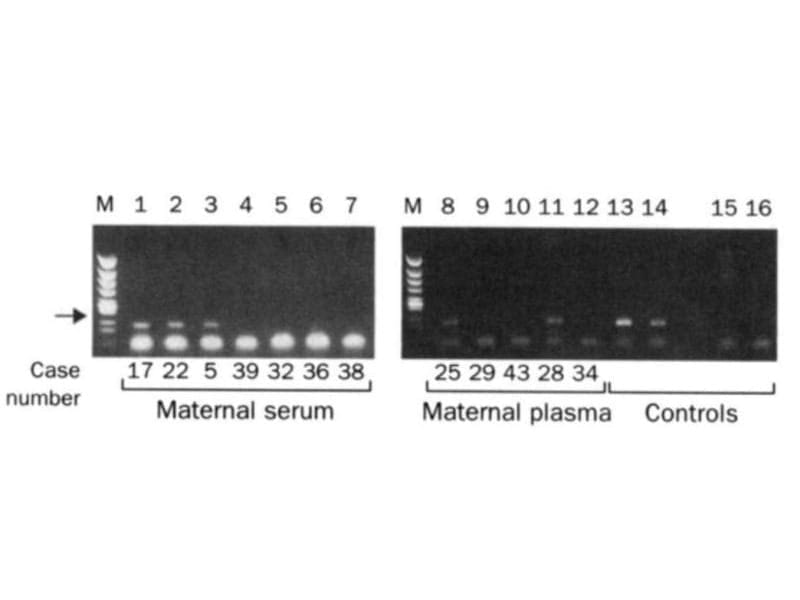

The two gels above spawned a multi-billion dollar industry that didn't exist prior to their publication in 1997.

While it may seem obvious today, you might find it surprising that we didn't know that fetal DNA was present in a pregnant mother's bloodstream until the late 1990's.

Prior to this discovery, genetic testing on fetuses was only performed if a problem was suspected with a pregnancy or if there was a family history of genetic disorders.

This testing was performed by karyotyping fetal cells.

You've probably seen one of these 'chromosome spreads' in a biology textbook where each of the 23 pairs of chromosomes are lined up next to one another.

This allows a geneticist to check that the chromosomes are intact and see if there are any abnormalities such as those found in Down Syndrome where patients have 3 copies of chromosome 21 instead of 2.

But, back in 1997, the process for collecting fetal cells was very invasive and was done using one of two techniques:

Amniocentesis (Amnio) - a 3-5" long needle is inserted into the mother's abdomen to collect 20 milliliters of amniotic fluid for testing.

Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS) - A 6" long needle is guided via ultrasound, either vaginally or through the abdomen, to obtain tissue from the placenta for testing.

Unfortunately, these procedures carry a risk and 1-2% of the time they can lead to the loss of the fetus.

Recognizing that there had to be a better way, Yuk-Ming Dennis Lo set about figuring out how to get at fetal DNA without having to perform Amnio or CVS.

He knew that fetal cells made it into the maternal bloodstream and that mother and child exchanged cellular material.

But he couldn't isolate enough fetal cells from the blood to do prenatal genetics with them.

Luckily, in 1996, Lo heard that a team in Switzerland had shown that tumors actually shed cell free DNA into the bloodstream and this tumor DNA could be detected using PCR and primers specific to the tumor DNA.

He reasoned that a baby, or more accurately, the placenta, was basically like a giant tumor and shared the bloodstream with the mother.

So, it made sense that it too should shed cell free DNA into the bloodstream.

The figure above is proof that Lo's hypothesis was correct and fetal DNA could be isolated and amplified from the blood of pregnant females.

In this figure, the arrow highlights a 198bp PCR product from the Y chromosome. Case numbers greater than 30 are pregnancies with female fetuses (don't have a Y), and case numbers less than 30 are male fetuses (have a Y).

Further technical advancements and the invention of high throughput sequencers have transformed this discovery into a popular pregnancy screening test.

Today, non-invasive prenatal testing is second only to oncology testing in sequencing market share.