It took 35 years for the first human Mendelian disease to be described

Mendel first described his laws of genetic inheritance in 1865. They were promptly ignored for 35 years.

Because, let's be honest, who gives a husk about peas?!?!

It probably also didn't help that his paper was titled, 'Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden.'

Which in English translates to, 'Experiments in plant hybridization.'

While this sounds exhilarating, it belies the foundational concepts described in its pages and Mendel's work breeding peas wasn't revisited until 1900 when his results were independently rediscovered and confirmed by E. Tschermak (peas), W. Spillman (wheat) and C. Correns (peas).

H. de Vries (flowers) also independently characterized plant genetics in 1900 but had to be told that Mendel scooped him 35 years earlier.

Oof.

So, what was it that Mendel discovered while studying peas?

He observed the physical traits of peas and how these traits were passed to their offspring after breeding.

Mendel established 3 genetic principles from these observations:

Segregation - Traits come in two forms but only one from each parent is passed to offspring.

Independent Assortment - The segregation of the forms of each trait occurs independently of any other trait.

Dominance - Dominant forms of each trait mask the recessive forms and they occur in a 3:1 ratio.

Mendel initially described these as laws, but we know now that there are numerous exceptions, so in genetics we often refer to Mendelian and non-Mendelian inheritance.

But in the early 1900's, the race was on to see if Mendel's phenomenon wasn't just some weird plant thing.

One of the biggest proponents of Mendel at the time was William Bateson.

Bateson is a forgotten figure nowadays, but he popularized the works of Mendel and also did some of the earliest work on genetic linkage.

He also became fast friends with a clinician scientist, Archibald Garrod.

Garrod was most interested in the biology of the diseases in his patients and had a particular fondness for chemistry.

This could be why he was so enamored with the color of his patients’ urine.

This curiosity paid off in 1899 when he first noticed a chemical aberration in the urine of patients with Alkaptonuria.

This is an ancient disease with symptoms being described as far back as 1500 BC, but one of its tell-tale signs is darkly pigmented pee.

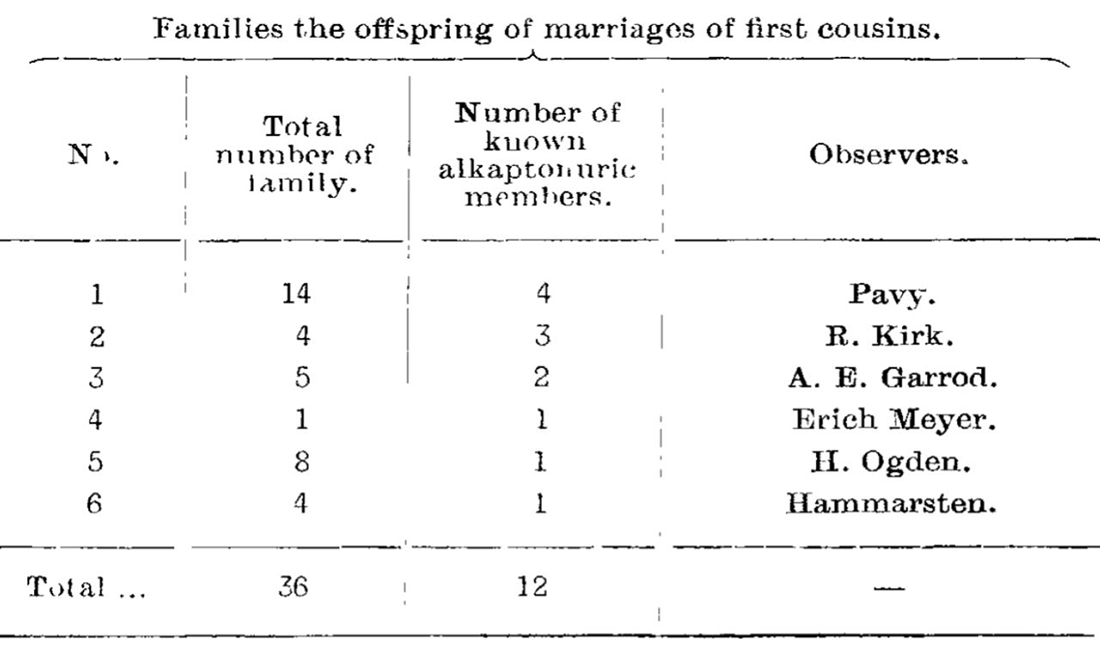

Garrod noted to his friend Bateson that this disease was found most often as the result of marriages between first cousins, and at Bateson’s urging, Garrod documented the incidence of Alkaptonuria in these families.

The figure above is the first evidence of a recessive Mendelian disease in Humans.

In the table you can see that in these families the dominant form of the trait is observed in 36 offspring, and the Alkaptonuria form in 12.

This perfectly aligns with the 3:1 ratio Mendel first observed in his peas!