If only Ponce de Leon had known about IL-11

Who knew that the fountain of youth was as simple as blocking inflammatory signaling through IL-11?

At least that’s what a recent paper has discovered in mice.

Humans have been trying to find themselves cures for what ails them since the beginning of time.

And it’s basically why the entire healthcare industry exists.

We’re all looking for ways to lead happier, healthier and longer lives.

This began in olden times with ‘healers’ mixing up potions that were purported to cure disease (or expel demons).

We still have those types of people.

But we also have science based approaches now that allow us to see if any of these treatments actually work.

While health and aging research has existed for as long as ‘healers’ have, we’ve seen an explosion of scientific research in this field in the last few decades.

We’re now starting to hone in on the genes and pathways that can be exploited to improve our health and lifespan.

Some of this comes down to us doing the things that we know we should be doing, like not eating too much junk food, getting exercise, being social and spending more time outdoors.

But there are also very likely to be things we can manipulate on the molecular level to extend the benefits we get from these activities even further!

And studies looking at changes that occur in our bodies as we get older have identified increased inflammation as a hallmark of aging.

Research in worms, flies and mice have shown that lifespan can be increased by inhibiting some of these pathways.

One of the best studied of these is the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway and mTOR is a protein kinase (phosphorylates things, usually to turn them on) involved in regulating gene expression, cell growth and metabolism.

It can be activated through a number of pathways including by pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-11.

The authors of today’s paper wanted to see what would happen to mice in the absence of IL-11 signaling and hypothesized that since IL-11 increases with age, its inhibition might be able to reverse some effects of aging.

And that’s exactly what they saw!

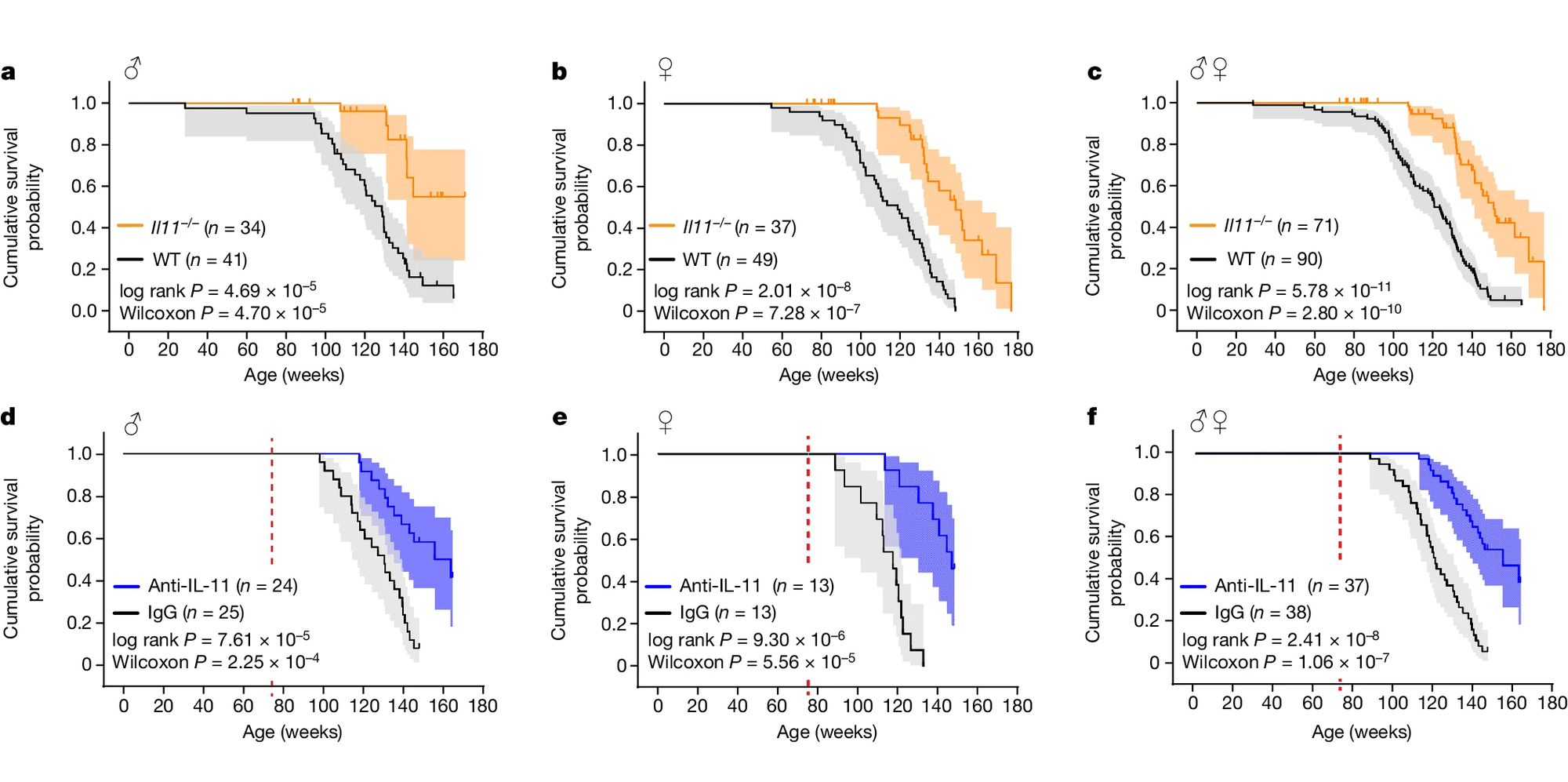

In the figure a, male (a) and female (b) mice who had the IL-11 gene deleted lived, on average, 20% longer than their non-mutant counterparts and this effect was mimicked by an antibody that blocks IL-11 (d,e,f).

But unlike other drugs in this space (like rapamycin) that only improve how long the test subjects live (but also with some pretty nasty side effects), this therapy appeared to make the mice healthier without any observed problems.

It’s important to keep in mind that this is early research in mice, but the authors point out that IL-11 therapies are being tested in the clinic for other disease states.

So, we could have some initial data on the health and lifespan effects of IL-11 inhibition in humans relatively quickly.