Genetic discrimination is still alive and well in the US

Did you know that before 2008, insurers could discriminate against you based on your genetic risk for disease?

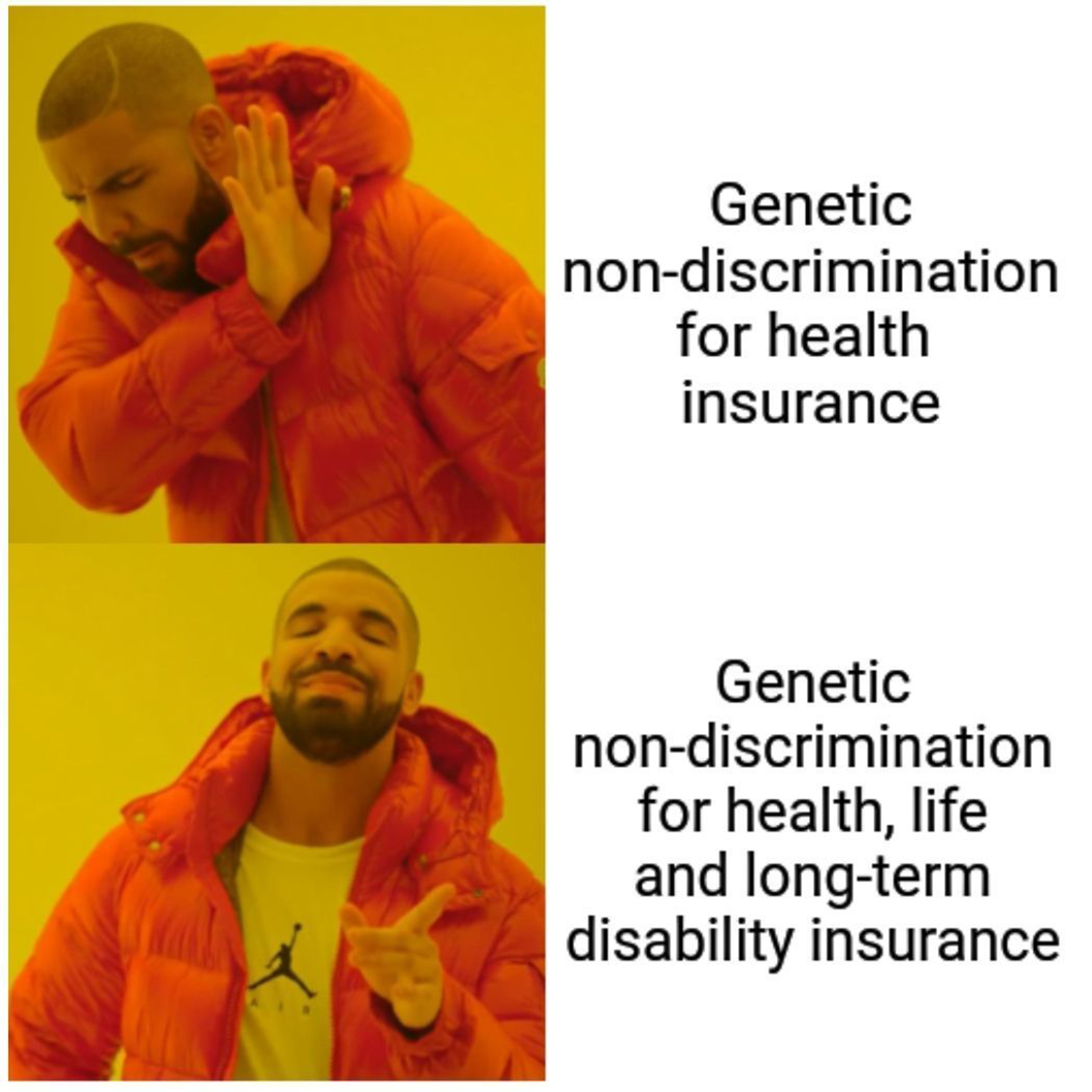

That ended when the Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act (GINA) was passed, but curiously, this law only applies to health insurance and employment.

These protections do not extend to life insurance, disability insurance, or long-term care insurance.

But we'll get to those in a minute.

You might be thinking that 2008 seems pretty recent for the passage of a major civil rights law, but that it coincides with when we 'finished' the human genome.

That kind of makes sense, right?

Unfortunately, genetic discrimination, like most discrimination, started a long time ago.

Beginning in the 1970's, some states forced African-Americans to get sickle cell tests with the intent to deny them health insurance or jobs if they tested positive.

These policies were blocked after 2 years but we had to wait 30 years for these sorts of protections to be enacted more broadly.

And that's because the use of widespread genetic testing opened everyone up to the same discrimination that had been perpetuated against African-Americans, so protective legislation was proposed and then put in place in 2008.

The politics here are a bit gut wrenching, but GINA has a pretty broad definition for what it considers a genetic test which is "an analysis of human DNA, RNA, chromosomes, proteins, or metabolites, that detects genotypes, mutations, or chromosomal changes."

GINA prevents insurers from denying anyone health insurance based on results from these genetic tests, and it prevents employers with more than 15 employees from denying anyone a job based on them too.

Wait, what? There's a 15 employee loophole?

Someone should fix that.

But what also needs fixing is how far GINA extends into the insurance industry because life, long-term care, and disability insurance companies can use genetic tests to deny insurance or raise rates.

These companies argue that they're selling risk based products and so it only makes sense that they're able to consider genetic risk when determining rates.

The problem is that genetics isn't deterministic, meaning, just because you have a mutation doesn't mean you're going to get a disease.

We know that genetics alone is very bad at predicting disease in healthy people, it's decent in determining a cause in someone showing symptoms but on average, 8% of people carry a pathogenic mutation, but only 7% of those will become symptomatic.

This is further complicated by the fact that gene-risk associations are highly dependent on the populations tested and so risk scores generally cannot be applied broadly or across ethnicities.