Ethnic Stratification: Sounds complicated, but in genomics it helps everyone

Ethnic stratification and why single reference based analysis methods aren't 'good enough.'

If you've done genetics for any amount of time you know that stratification of populations is important for getting useful information out of them.

But if you're not a geneticist, it might be a good idea to explain why this is true.

Stratification is a statistical term that basically means "divide your data into subgroups."

In genetics, we usually start with age, gender, life style/exposure, and ethnicity.

The reason for doing this is to be able to determine if subpopulations within a dataset are more or less likely to have whatever it is that you're looking for.

This is usually a measurable trait.

Sometimes this is a common trait like height or eye color, but in healthcare, we're usually talking about disease traits.

So, figuring out if a specific gender, age group, or ethnicity is predisposed to a disease is important, but because diverse populations have mostly been absent from clinical studies, it’s hard to identify important markers of disease in them.

While we know ‘variants’ or ‘mutations’ can contribute to disease, how these contribute to disease can differ vastly depending on someone’s ethnic background.

Variants in one ethnicity may not matter in another ethnicity because mutations elsewhere can compensate in some way for those changes.

So, how you go about determining what is or is not a variant can have a serious impact on the conclusions you draw from a dataset.

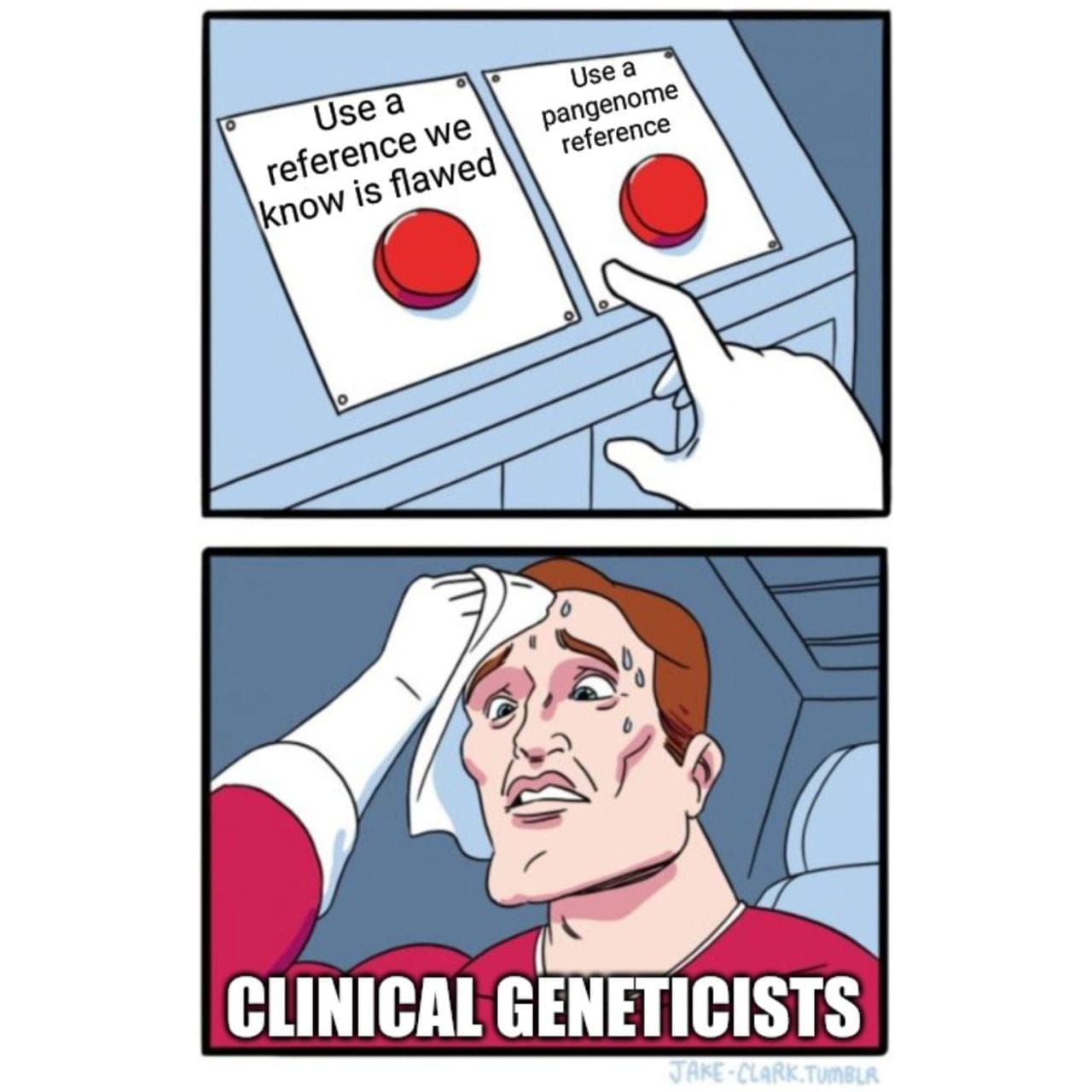

As it stands now, most variants are determined by comparing a patient’s genetic sequence to a ‘reference.’

The reference here is the one determined by the human genome project.

This was supposed to represent the sequence of the average healthy human, but we know now that the bulk of this DNA was provided by a mixed race male.

So ‘variations’ from this reference might not be super accurate if we’re trying to determine the importance of a variant in a different ethnicity.

This bears out in multiple clinical evaluations with a recent survey determining that the number of variants of unknown significance (VUS) was markedly higher in Africans (45%) than Caucasians (32%).

A good chunk of the VUS-ness here has to do with whether the ‘reference’ was appropriate for an African vs a Caucasian, but it also has a lot to do with the fact that most genetic studies have been done in Caucasians, so we already have an idea which ‘variants’ are significant in that population.

Fortunately, we’re seeing progress on multiple fronts here with most associations and government institutions calling for greater diversity in clinical trials.

We also have a human pangenome reference now which more accurately characterizes the ethnic differences we see in our genomes. It’s not completely done yet, but pangenome based variant calling pipelines are available.

So the question is: how long will it take to integrate these updates into clinical practice?