Colorectal cancer has found a new best friend. Spoiler: It’s a bacteria from your mouth!

Long-read sequencing can now help us figure out what makes the Fn bacteria found in CRC tumors tick.

Our bodies host trillions of bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

A trillion is a hard number to wrap your head around but it gets even more mind blowing because we don’t have just one microbiome.

Every surface, crack and crevice creates a distinct ‘niche’ that is colonized by different microbes.

And the bugs found in your mouth are very different from the ones that hang out in your arm pits or gut!

Our microbiomes are important because, in most cases, we maintain a mutualistic relationship with these tiny invaders.

We give them food and shelter, they give us metabolites and perform chemistry that the cells in our body can’t.

But sometimes these relationships go awry and microbes that are helpful friends in one place end up being notorious enemies in another.

We’ve known for a while that the bacteria Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fn) is found predominantly in the oral cavity and is usually absent from the gut of healthy people.

However, in 2012, Fn was found co-habitating within colorectal cancer tumors.

Tumors, unsurprisingly, can also create niches, so colonization of tumors in the colon with bacteria isn’t that surprising.

But colonization with something like Fn IS because that bacteria isn’t usually found in the colon!

Why Fn bacteria is found in CRC tumors and how it gets there has been something of a mystery.

It was hypothesized that they could perform useful functions for tumors, promoting their growth, giving them the building blocks they need to be all cancer-y, and in some cases, soaking up cancer drugs and preventing them from getting to the tumor to kill it!

This mystery persisted because the sequencing tools we’ve had at our disposal haven’t been good enough to fully genetically characterize these bacteria.

Thankfully, long-read sequencing exists now and we can easily create whole genome sequences to figure out what makes them tick.

And that’s exactly what the authors of today’s paper did!

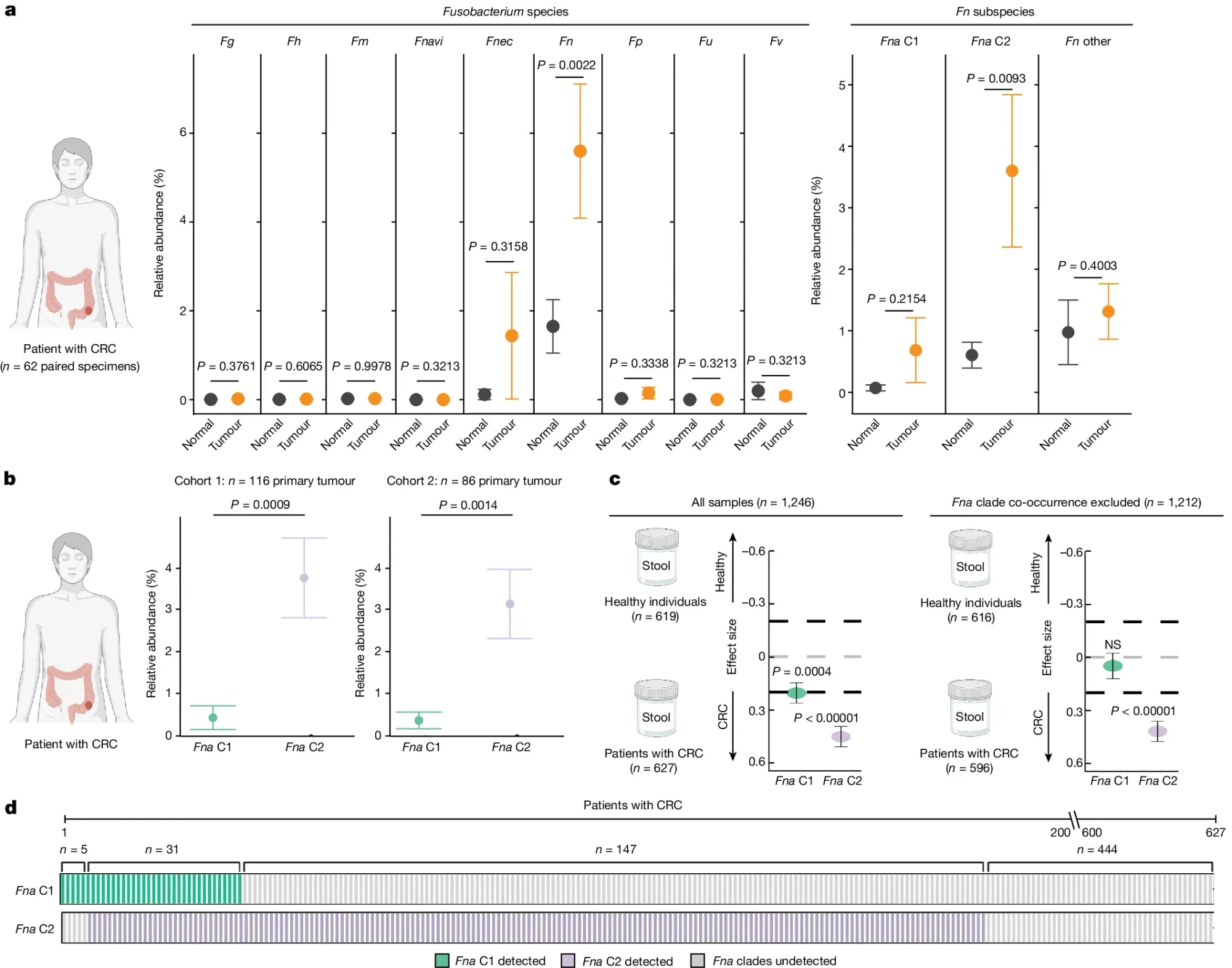

In the figure above they a) sequenced normal and CRC tissue to see which Fn subspecies were present in the gut and identified a specific sub-species of Fna, C2 (Clade 2), that was associated with CRC tumors, b) they expanded the analysis to two additional CRC cohorts showing enrichment of Fna C2 (purple) in CRC but not Fna C1 (green), c) Fna C2 is more closely associated with CRC and d) Fna C2 is present in the metagenomes of most CRC tumors.

The researchers also show that addition of Fna C2 to a mouse model of CRC promoted tumorigenesis pointing to a role for Fna C2 in increasing cancer risk and identifying it as a potential target for therapeutic and diagnostic development.